Be aware there are images of real patients in this post that may upset sensitive viewers.

You’re not going to be able to save every animal. That’s just the truth. There is no way around it. Sometimes you’ll get an animal in that is hurt so badly that it doesn’t stand a chance and the only thing to do is bring it to a vet for humane euthanasia. Sometimes you’ll get one that is hanging on by a thread, and you try everything you can to help it survive, and it’s gone by morning. Sometimes you’ll have a patient who’s been recovering nicely for some time and suddenly, inexplicably, takes a turn for the worse. Most of the time, it’s not your fault, but some of the time, it will be. You might know this right away, or figure it out later, or you might never know what little mistake you made.

The hardest ones are the ones you know are your fault, not that any of them are easy. The best thing to do in those cases is to learn from it. Whatever it was you did wrong, don’t do it again. Every skill comes with a learning curve, and unlike most hobbies, wildlife rehabilitation’s consequences can be extreme. Nobody dies if you knit a row wrong in that scarf you’re making. Nobody dies if you can’t get the shading right on that painting. In general, nobody dies if you miss a step in that dance routine. But when your hobby, your passion, is helping sick and injured wildlife, you’d better get used to death. Develop coping mechanisms that are healthy and sustainable. Whether it’s going through the five stages of grief for each and every animal, having some kind of burial ritual or prayer, or fully detaching and rationalizing, you need to figure out something that works for you. Because even if you do everything right, death will still come knocking for some of your patients.

I knew I wanted to write a post about patient death for a while, but I felt I shouldn’t write it in close proximity to any experience of it, so that I could come at it with a clear head. It’s winter at the time of this writing and it’s been a while since my last intake, so all my current patients should be well out of the danger zone, and I shouldn’t have any new patients for a few more months. The time is now to talk about my first full year of rehabbing and how death has factored into it.

I don’t think the absolute eventuality of dealing with death is something that the rehabber classes really prepare you for. I don’t even recall if it was mentioned in the class I had to take to get my rehabber license (it probably was, but I don’t remember what they said, so it can’t have been that helpful), but there was a small section about it in the study manual they gave out beforehand. The manual mainly touched upon how to decide if an animal needs to be put down due to severity of injuries or quality of life if unreleasable, and that you would have to consider practical things like methods and disposal (though it didn’t get into either in any sort of detail). It didn’t talk about the emotional toll it takes on rehabbers, except to ask the rehabber-to-be if they were prepared to deal with it (without actually telling them how).

I’m no stranger to death, and most people by the time they’ve reached adulthood have experienced some kind of loss, whether it’s a childhood pet, a family member, friend, or something else. It’s rather a grotesque thing to be good at, dealing with death, but like anything else, practice makes perfect. That may sound a little bizarre, but it’s true. All deaths will affect you in some way, but the first ones, the earliest ones, and the ones that are different in some important way than the ones you’ve already experienced are the ones that shape you and never let you go. Eventually, as bad as it sounds, you’ll kind of just get used to it. You jump straight to acceptance in the grief stages and just get on with what needs to be done. You might still cry about it, but you can’t let it stop you for too long, because chances are you have other patients who are still alive who need you.

Don’t confuse a shortened grief period with bottling it up and ignoring it and hoping it will go away. This kind of thinking only hastens rehabber burnout.

One thing that’s majorly different between patient death and any other death you will deal with in your life is that most other deaths aren’t going to be things you’re actively working to prevent in a very specific way for that specific being. It’s different feeling sad that a person or pet in your life passes away compared to a patient. With the former, death is a thing that happens to them, something you don’t have control over, yet something you will see the impact of forever. Your life without them will be markedly different. With the latter, death is something you have spent time, energy, supplies, and money actively trying to prevent. Even if you did everything you could and there was no saving them, it still feels like you’ve failed. Even if you did nothing wrong, you still feel guilty or personally responsible for their fate. You won’t see what the environment’s life will be like without that particular animal. You won’t know their death’s precise impact on that animal’s habitat, though you can hazard a guess at the general consequences (lower overall population due to one less animal reproducing, its food/prey species increasing population or its predators decreasing and potentially becoming unbalanced, etc.).

Now that I’ve talked about death more generally, I’m going to share a few examples of patients that I’ve lost, and how I felt at the time, and what helped me move on.

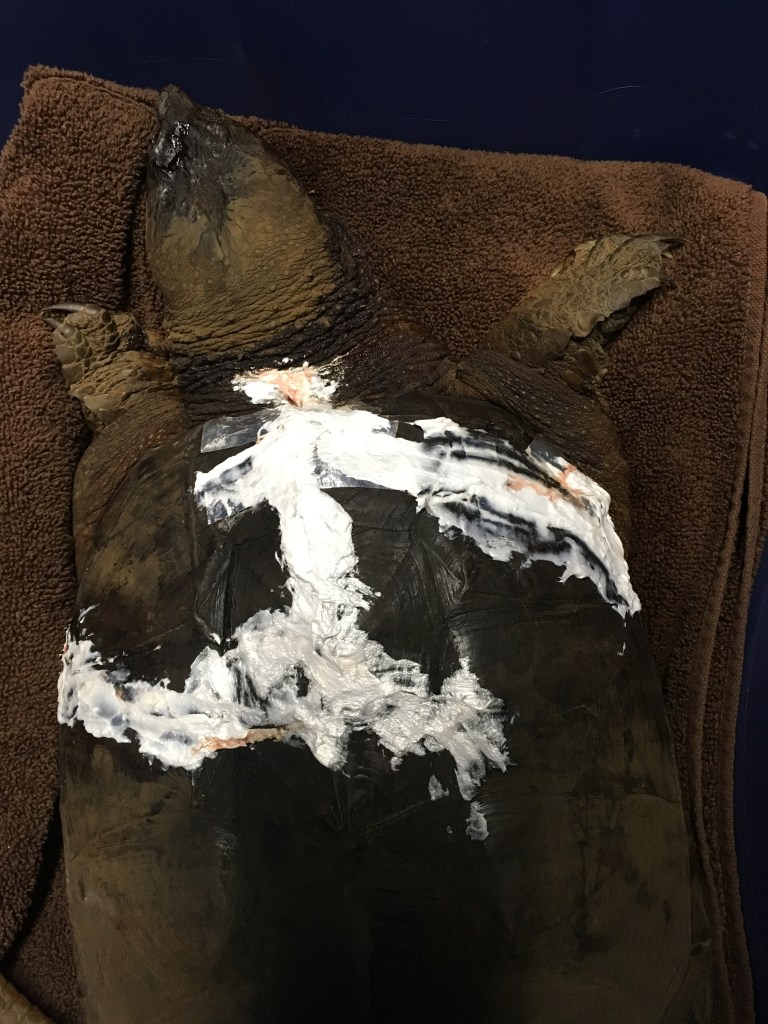

My first patient death came while I was still apprenticing with my mentor, Pam. I had come over to do my first major shell repair on a real patient. This one was a huge snapping turtle whose shell was crushed pretty badly on the back. I learned and actually executed all the steps in treating the turtle, from hydration to cleaning to shell repair to medicine. I can’t claim that I was good or confident at any of the steps, but I did them, and I felt accomplished. Pam was scheduled to leave town the next day and so suggested I take this one home and give it its shot if it survived the night and continue its care until she got back the following week. To be fair, I kind of knew this one was a goner. Its injuries were very severe and it wasn’t fighting us very much when we were putting it back together. I had already seen several of Pam’s patients that looked dead until you poked them and then they moved, so the fact that it wasn’t moving very much once I got it home didn’t concern me. I poked it a few times throughout the night and it moved, but barely. I honestly couldn’t tell if it was dead yet, but I wanted to believe it was still alive. I wanted my very first patient to survive, as if that would somehow be a significant portent of my future rehabber success. The next morning, though, it was dead. Totally unmoving and starting to stink. Poking it and lifting it up elicited no response. I still didn’t want to believe it, but I knew. It had probably died on the car ride home and the movement/sound I observed was just residual reflexes and air escaping the lungs with nothing working to hold it in. Now I had another problem, though. What do you do with a dead turtle that weighs probably 20 pounds? So, I called Pam and she said that I could either bury it (and I would have to bury it deep enough that animals wouldn’t smell it and dig it up) or put it in a garbage bag and take it to the curb. Well, we have coyotes and fishers and all sorts of other animals where I live so I knew there was no way I’d get that thing deep enough in the rocky, hard dirt of my yard without an insane amount of digging. And, I was already exhausted from all the hope and disappointment of my first patient dying that I physically and mentally could not handle giving this thing a proper burial. Just like that, it went from a life I wanted to save to a thing to dispose of. I needed it gone as soon as possible to get over this one, so that I could just not have to think about it anymore. I had my husband help me double-bag the carcass and I put it in the trash can. The garbage men weren’t due for a few days, and it was hot out, so that can reeked for months after that, no matter that I bleached and hosed it out multiple times and left its lid open when it was empty to air it out. An unceremonious end to a life, but that was what I needed in order to move on. I had been in denial for so long and then jumped straight to acceptance, so I just needed to be physically done with it in order to be mentally done with it. For two days after that, I had nightmares that the turtle was actually still alive and that I’d put it in the trash and it was furiously trying to escape, or else it was slowly suffocating. I actually went out and opened the trash can lid and the wave of stink that hit me was proof enough that my brain was playing tricks on me. After that, the dreams stopped, the garbage men came and took it away, and I didn’t have to think about it anymore. In this case, it was moving on with practical concerns that helped me move on emotionally.

Sometimes, death is not the end of a life. I’m not talking about turtle heaven, here, though it would be nice if there were such a place. The reason most turtles wind up in rehab is because they were crossing roads trying to find a mate or lay eggs and got hit by a car instead. One of the things you have to do when intaking a turtle is to determine its sex, and if it’s female, gently palpate for eggs. Some rehabbers maintain that the turtle should be induced to lay immediately so that the body can begin healing itself (and stop expending energy on the eggs) and so that the turtle doesn’t retain the eggs and become egg bound, a potentially deadly condition. Others believe inducing is a last resort and you should let the turtle lay them naturally to reduce stress on the turtle and complications from induction drugs. Regardless of which way you lean, incubating eggs and caring for hatchlings is something that turtle rehabbers will most likely wind up doing. A turtle is not always going to survive long enough to get the eggs out one way or another, and this was the case for one of my patients this year, a painted turtle. She hadn’t gotten to wherever she was planning on digging her nest yet when she was hit by a car, and her head was so crushed that humane euthanasia was the only option. I was surprised she survived as long as she did given how badly both her head and body were shattered. I brought her to the vet, who performed the procedures to put her down and extract the eggs for me. I incubated them, and out of seven, one of them hatched. I’ll be caring for this hatchling until the spring when I’ll return her to her mother’s pond. I accepted the mother’s death immediately, and hoped that the eggs would not have taken so much damage in the collision as to make them not viable. It would have been great if more than one had survived from the clutch, but at least I have that one. There is some solace and maybe a small amount of beauty in saving the baby turtle that would not have come into existence without intervention and watching it grow for a few months before setting it free. In this case, looking to the future and being grateful for what I did have and who I was able to save is what helped me move on from who I wasn’t able to save. Don’t forget to count the wins; it helps when you’re dealing with losses.

One death that I want to make sure that I mention happened many years before I decided to become a rehabber, and before I fully knew what one was. I was on my way to work, and I saw a painted turtle on the side of the road. Or, rather, I saw a brown blob that looked too weird-shaped to be a rock and I swerved to avoid hitting it as it was partially in the road/in the exit/U-turn ramp that I was about to take. As I passed it, I saw that it was a turtle, and I so I made another set of U-turns to get back on the other side of the divided highway going the right direction and slowly enough that I could actually stop this time. I picked it up, and thankfully, it was still alive, but its shell was pretty crushed. This was in the pre-GPS/smartphone days where you had to look up directions on a computer and print them out, and I was pretty close to my work where I knew I could do that. My boss happened to be in the parking lot as I pulled up and jumped out of the car with this injured, bleeding animal in hand. At first, my boss thought I’d brought in one of my pet turtles, unbidden, to share, but when I told her what happened, she gave me immediate directions to a local veterinarian. So I jumped back in my car without even going inside and drove there. The vet took it in and looked at it (may have given it some medication, I don’t remember), but then wrote down a phone number of a rehab center, which I called, and then with their directions, I drove to immediately and dropped it off. This whole process took over an hour, maybe two. I wasn’t making a lot of money at the time, but I still gave a donation, and somewhere in my mind, I had the idea that the experts had it and so therefore everything was going to be okay. I got a call a couple days later that the turtle hadn’t made it. They told me that it was much more comfortable in its final hours because I brought it in than it would have been on the side of the road, and thanked me for stopping to help and for driving it there. I thanked them for trying and then hung up. I still couldn’t believe it at first. Logically, I knew this was a possibility. You didn’t have to be an expert to tell that its injuries were probably fatal. But I was still upset. I was angry. First, at the rehabbers, who I was momentarily convinced hadn’t done all they could and had somehow screwed something up, then, at the vet for not knowing what to do with a turtle, leading me to waste precious time driving it around. Then, at myself, for not spotting it sooner, as if the couple of minutes my turn-arounds took would actually make a difference. Finally, I found the correct place for my anger: the person who hit the turtle and either didn’t notice or didn’t care enough to stop and help it, or worse, did it on purpose. And then, all of a sudden, I was sad. I knew it wasn’t really anybody’s fault, and then I cried. I don’t think I told anybody at the time because I thought people wouldn’t understand why I was crying over a turtle that wasn’t even mine. And when I was done crying, that was it. It was over. I gave my pet turtles some extra treats that day, and made sure I always drove slower on that section of road, but otherwise, I was finished grieving. In maybe an hour, I had moved on. In retrospect, I realize this experience taught me an important lesson for my future as a rehabber, and not just about the possibility of death, but the importance of communication. I was sad to learn that the turtle I’d stopped to help didn’t make it, but relieved to know the truth. If they hadn’t told me, I’d probably still be wondering about it. Few things make me more anxious than unanswered questions, and so I try to provide realistic prognoses to finders and update them in a reasonable amount of time about the fate of “their” turtle. Even if it’s not good news, I know I would want to know what happened, so I make sure finders do. In this case, stopping to really feel my emotions and accept them is what led to me moving on.

Sometimes, you’ll witness a lot of deaths in a short amount of time, and it will be hard to take. I recall one day where my husband and I were out and about and I got a turtle call, so we turned the car around and went to pick up an injured turtle. On the way there, we saw probably a dozen dead turtles of varying sizes on the sides of the highway. We turned around several times to check the bodies going both ways on the divided highway, just to see if any of them could be saved. They were all long dead and too far gone to even hope for saving any eggs. It was really, really sad. Then, we picked up the turtle I’d gotten the call about, and that one was a goner too. I knew before I started working on him that he probably wouldn’t survive the night, and he didn’t. It was a bit much, all that death in one day, and so I hugged my husband and I cried, and then I felt better. In this case, knowing I had the love and support of my family to comfort me when I had to deal with death is what helped me move on.

In summary, there is no one magic recipe to follow to make accepting rehab patient deaths any easier. Each situation will be different and you may react differently to deaths depending on the circumstances surrounding them. Regardless of how you feel when it happens, your feelings about the deaths of your patients are valid (even the feeling of relief that you no longer have to care for a particularly demanding patient…don’t feel guilty for acknowledging the amount of work you put in if you’ve done everything you could but you’re glad you don’t have to do it anymore). You won’t necessarily go through all five stages of grief for every patient, but it’s still good to know what they are and recognize where you are in them (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance). It’s good to have a plan for the practical repercussions of not being able to save an animal. It’s also good to have people you can talk to when losing a patient gets you down; it could be a friend, family member, or another rehabber. It’s good to be able to still see the big picture and focus on the present or the future. You won’t necessarily cry every time a patient dies, but it’s good to allow yourself to do so when you need it.