I started during the slow season, when there were relatively few turtles left in Pam’s care. The ones that remained were either injured late in the season or their injuries were so severe that they wouldn’t be recovered soon enough to be released before it got too cold out. Turtles can hibernate, but they need to be healthy enough to do so. The ones left had head trauma, jaw damage, or an infection. Poor things.

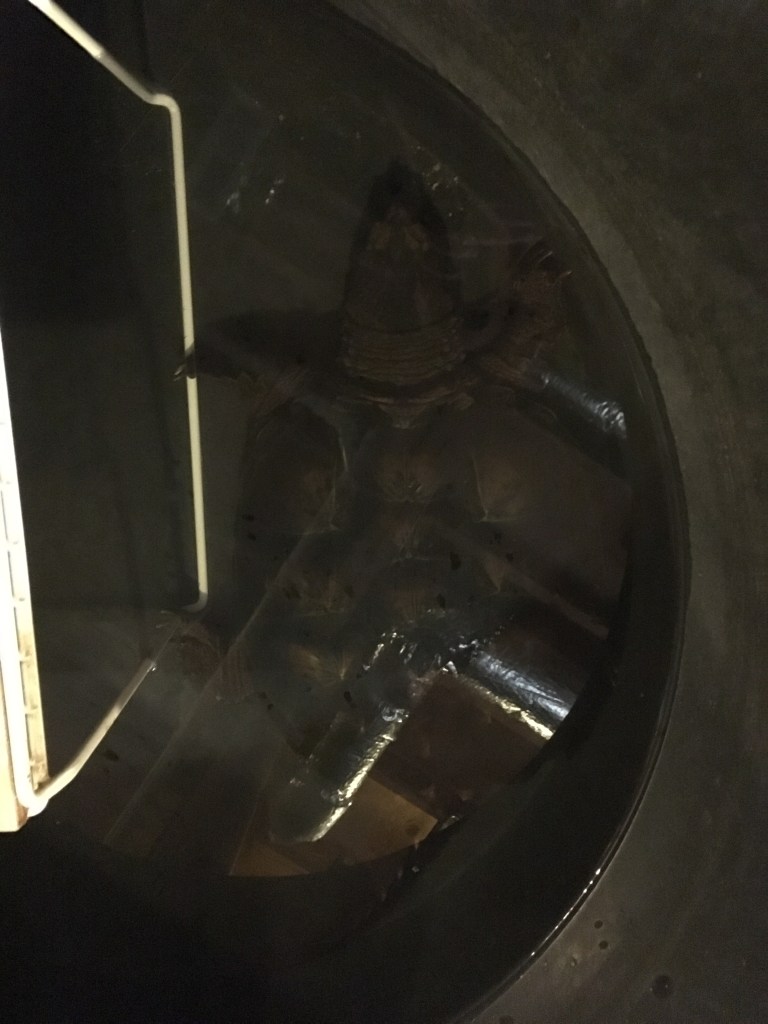

First up was feeding the snapping turtles with the broken jaws. There were a couple of them, and their lower jaws were both split down the middle, so they couldn’t bite. What this means is that we had to pry open their jaws and hold them open with wooden dowels, then use long metal tongs to shove raw fish down their gullets, and put them back in the water so that they could swallow it the rest of the way. Aquatic turtles need to be in water to swallow, something I did know from having them as pets, but I’ve never had to force-feed alligator snapping turtles before, so that was an experience! It took the two of us to wrangle them and keep the turtles still while feeding them. I learned that wrapping up feisty turtles in towels and placing them vertically in a milk crate with more towels wedging them into place is a good way to immobilize them. Not just from their limbs being pinned, but turtles have low circulation, so if you place them vertically instead of horizontally, their blood starts to pool at the bottom of their bodies away from their heads. It doesn’t hurt them, especially since it’s only done for a little while for treatment, but it makes them somewhat more dazed/lethargic/calm temporarily. As soon as they’re back in a horizontal position, they’re back to normal. I also learned today that snappers can go months without feeding if they have to.

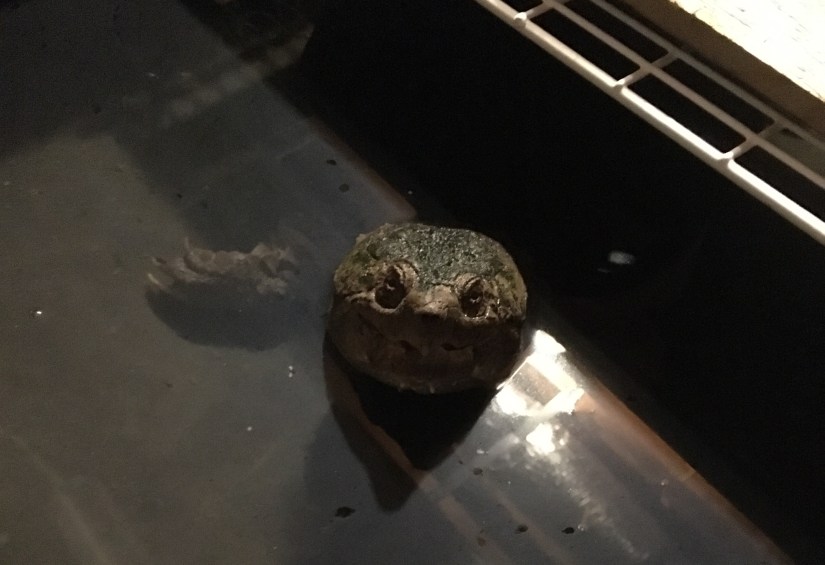

I also fed the ones still recovering from head trauma. I basically dangled raw fish and wiggled it half above, half below the surface of the water, using long metal tongs, so that the turtles could get them. The head trauma ones didn’t have great aim or control, so giving them fish one at a time rather than just letting it sink to the bottom ensured they’d actually get fed. Live fish they wouldn’t be able to catch on their own at this point.

The final thing I did was assist in minor surgery on a painted turtle with an ear abscess (an infection that causes a swollen lump filled with infected fluid). Pam had already done an initial drain of it and put the turtle on antibiotics, but the ear has to be cut open a few more times, a week or so apart, to drain/scrape out any further pus the infection creates. The ear can’t heal over with pus/gunk still inside it or the infection won’t go away. Pam did all the surgical work, and I held the turtle. I learned that when working on the head of a turtle that doesn’t want to come out of its shell, it is easier to pull the head out if you hold the turtle vertically upside down, so gravity is assisting you. You still have to pull, obviously, but it’s easier that way. The hard part is getting the head to stay out. You can grasp behind the head gently with your fingers and/or wrap the turtle in a towel and place the edges of the towel alongside the neck so that it blocks the head from being pulled back in. I feel like my husband, Bobby, could invent some kind of turtle sling to suspend and secure turtles needing cranial attention, if he wanted to. He’s very good at building/engineering/math stuff, and built most of the turtle setups I have at home for my pets. I have a sneaking suspicion that if I do become a fully-fledged rehabber, he’ll be doing some more engineering around the house.

So interesting as I learned so much this past week

LikeLike